I once flew to Rome for dinner. In sustainability aware 2025, it seems excessive to say so.

On another occasion, with the fabulous Fiona Gordon who currently helms Ogilvy & Mather in London, I did also go all the way to Singapore for nine-hours to run a tone of voice workshop. We travelled from London via Amsterdam. The tone of voice we midwifed with the client was probably ‘weary’, almost certainly ‘jaded’. After our six-hour meeting, we had just time to stumble along along the shore front. Pitch and management duties back in Canary Wharf meant we then bolted for the airport. Looking back, ‘madness’ is putting it politely. A day longer and we’d have witnessed the island’s first ever F1 Grand Prix.

But the fly-to-Rome dinner trip was quite special. It all came about because of a coffee brand. Illy caffè is based in Trieste, an enigmatic, coastal city, brooding at Italy’s eastern extremity. The company’s rich, dark blend, twice the price of other coffee, stood proxy for the city’s allure. Family owned, eccentric, but run with exacting precision, the name ‘Illy’ is universally known from the top of Italy’s boot to the heel. Glossy, silvery tins of its espresso stand guard as expensive grown-ups in the coffee aisles of Italian supermarkets. In the Illy factory, at one point, the raw beans were furrowed down to a single line, travelling at speed towards the roasters. I saw this on our tour. Maybe it still happens. On our familiarisation visit, there was an elderly man whose job it was to flick away any beans that – to his eye – didn’t pass muster. In the brief seconds that I watched, he dispensed with around one in every three or four hundred, pinged away expertly with a blur of his index finger. It was hard to spot why they failed to meet his approval.

Illy had appointed a charming, urbane marketing director. Always immaculately dressed, he was blessed with magnificent hair. I never fully understood his remit, nor exactly the problem we were to solve. Vaguely, it seemed to be about justifying the price premium with stories of obsessive quality control. More generally, perhaps our job was simply to spread word and introduce Illy to the UK. There was an eager audience. In the middle 90s, London was falling over itself with lust for ‘real coffee’. Whatever the exam question we were supposedly trying to address, it fuelled many hours of fiercely intense conversation between our glossy haired client and the patient planning director, Jim Carroll, and Gwyn Jones, BBH’s managing-director-elect. At some point, I knew well, we would have to conjure up some ads. Jim and Gwyn were the ‘A team’. I didn’t want to disappoint. When, eventually, they decided to put the ball on the spot in the shape of a brief, all eyes would be on me to tap in creative work that matched its laser focus. The expectation would be that my efforts would thunder past the goalkeeper of prosaic reality and into the net of dreamy success. Protesting it was ‘only a coffee’ wouldn’t cut it if the work was crap.

There were nights when I didn’t sleep. Anticipated pressure can be a cruel bedfellow, jabbing you in the panicky cortex, when your sinews scream for deep peace under the duvet.

In the end, fate took a different turn. BBH received an embarrassed call from the Illy marketing director. It was, how could he put it, complicated. Senor Illy had had dinner. In California. With Francis Ford Coppola. And it was a special dinner, and they had got along so well. So you know that marketing budget of two million dollars..? Well, Senor Illy had given it to Mister Coppola. Every last cent.

Ah. Yes. Hmmm. There are some conversations to which the response can only be one’s most expressive shrug. Game over. Despite vague contractual obligations, the marriage between Illy and BBH was quietly annulled and both parties separated, not without rueful sighs in London. Time slipped past.

And then, out of the blue, an invitation winged its way to Kingly Street. Would we like to send an emissary to attend the launch ceremony of Mr Coppola’s Illy film? We had heard only the sketchiest rumours about the production. Here was a request to join the Illy family in a swanky villa in Rome’s Trastevere, for dinner and a screening, at which the director himself would be present. To a generation of a certain age, it was a Blue Peter pencil of a consolation prize, with intriguing bells attached.

Gwyn and Jim were both off saving the BBH world somewhere, so it fell to me to wing it to Rome. I arrived in the late afternoon to a city coated in a hot musk of summer. The nondescript hotel sweltered. Lush trees shimmered in the foregrounds of gauzy, epic vistas. Streets swarmed with vengeful Vespas and predatory taxis, their freneticism made languid in the haze. As the shadows lengthened, I cabbed to Trastevere and a fabulously appointed villa, some way up from the main piazza. Shaded, perfectly proportioned and emitting deep purrs of extortionate property value, this was a statement venue. Queuing to show my invitation with a small group of others, I was suitably impressed.

Around a hundred of us slowly gathered amongst the trees in the garden. Graceful waiting staff hovered with micromillimetric glass refills and precision bombing runs of tiny canapés. I chatted with one or two people, trying to gauge the milieu. Their cladding was instructive: immaculate black suits and dark ties for the men, formal summer dresses from name designers for the women. They could easily have been a ski crowd from the smartest of resorts, recalibrated in late May plumage. Any names I picked up in murmured introductions were long and flowery. This, I decided, was a tribe of youthful Italian aristocracy, oozing wealth, entitlement and superiority.

As dusk became darkness, we began to ebb and flow through the villa’s open doors. An exemplary buffet was dished from table-clothed altars, parked among the trees. I attempted conversation with one or two of my companions as we forked exquisite offerings from plate to mouth. From memory, they possessed indeterminate marketing roles in a succession of Italian food or drink companies. Observing their glances over my shoulder, they appeared to know each other well. The atmosphere spoke society wedding. Strained, polite, circling the starring reason for our gathering, my fellow guests were clearly not anxious to pursue exchanges with an oddly out-of-place Englishman.

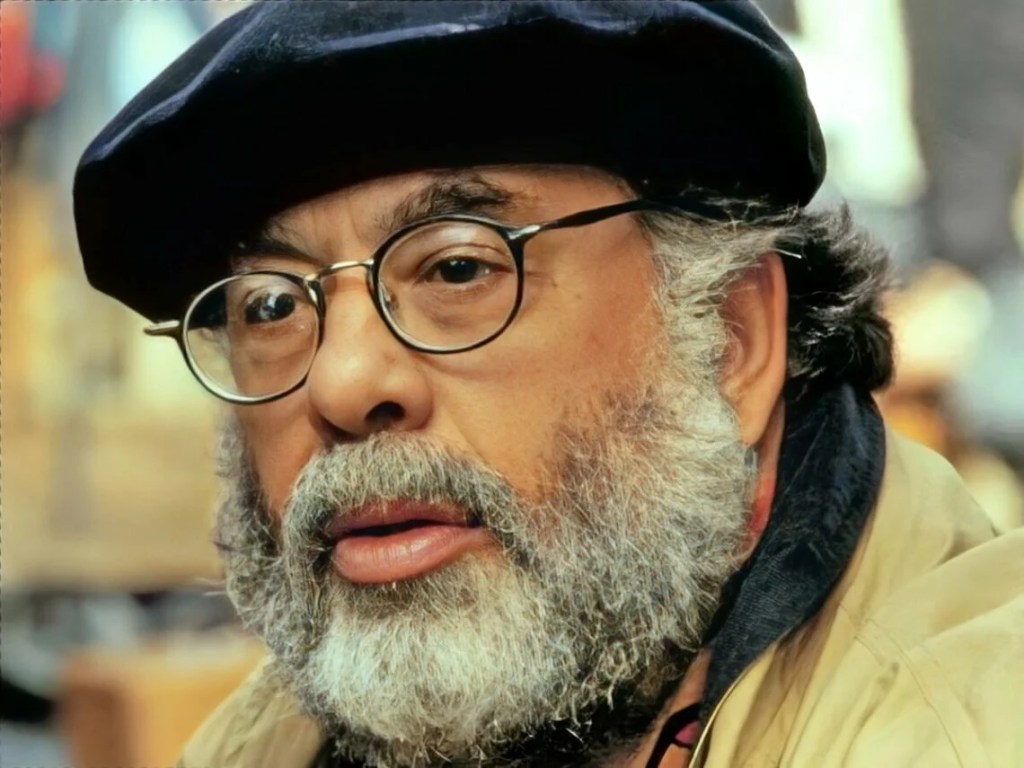

Come the conclusion of dinner, as whole, hollowed-out parmesan cheeses were rolled back to whichever kitchen they had come from, the main event loomed. Before we gathered in front of the huge screen, carefully erected as we ate, there was a meet and greet line-up. I queued with the crowd. The first exchange was with the marketing director, who flicked his glossy locks with gratifyingly shy awkwardness. Other, subsequent company luminaries grabbed my hand and smiled. Senor Illy was the penultimate stop, a silver-haired patriarch with the looks of Paul Newman and the handshake of a torque wrench. He looked straight through me to the more interesting prospect following behind. I shuffled on and found myself standing in front of Francis Ford Coppola.

He wasn’t wearing a beret, but his dinner suit was artfully, admirably crumpled. He looked at me with a quizzically benign squint. His beard jutted. These were my seconds with greatness. This was the genius behind perhaps the most impactful films I had ever seen and still, many years later, have ever seen. The Godfather, The Godfather II and Apocalypse Now! are deservedly celebrated for their indelible brilliance and will be forever more. Visionary, compelling, viscerally searing and yet elegantly poetic, I was only too aware of the intelligence of the director in front of me.

“Ah, I, er, work at the ad agency in London where we have been…where we were working with the company,” I mumbled. “I’m really looking forward to seeing your film.” I stopped. He looked at me questioningly. “I’m wondering,” I faltered, “what is your film all about..?”

After a second, a slow smile of warmly conspiratorial amiability spread across his face like a sunrise. He leant forward. I looked into his eyes. “D’you know,” he said quietly, “I really have no idea at all.” His gaze held mine.

“But,” he concluded, “It was a lot of fun to make.” He lowered his eyelids in polite dismissal and I turned back to join the crowd.

Twenty minutes later, Senor Illy pressed ‘play’ on a theatrically cumbersome device in front of him and we all watched the film as it ran for one minute and fifty seconds. The version we saw is below. There are obvious narrative strands and a story within a story. Characters abound. Theatricality is evident. One could attempt all sorts of analyses. But, speaking honestly, as to why the film belongs to Illy or what it says about the coffee…

I’m with Francis.

Love it as always. Really enjoyed seeing the film too – thanks for that.

Xxx

LikeLike